Cairo’s Tahrir Square presents a riddle. This irregular expanse of land and surrounding building surfaces has acquired a central symbolic place in Egyptians’ collective memory, demonstrated by its recurrent use for decades as the primary site for voicing people’s grievances and proclamations. To its romantics and its detractors, what happens in or around Tahrir Square remains crucial as an index to some perceived collectivity. Despite being a twentieth-century addition to a city with a much longer history, and despite the presence of older squares with central locations and considerable sizes (including Maydan Ramsis and Maydan Abdin), Maydan al-Tahrir now sits uncontested atop a hierarchy of symbolic urban spaces in Cairo and other Egyptian cities. How did Tahrir Square acquire such symbolic status? When protesters repeatedly took their grievances to Tahrir Square since January 2011, and in previous waves of street actions over decades, none declared going to confront a specific institution or associate with a particular building in the square. What then did they imagine occupying when there?

A credible historical account for how Maydan al-Tahrir initially attained its status as the “people’s square” is outlined below. But while necessary, this remains insufficient to fathom the confounding riddle: What in or about the square sustains its symbolism in collective perception for decades, when it does not seem to be embodied in surrounding structures or their interrelationships? Can the city be conceived, carried and conveyed exclusively in people’s memories, imaginations and narratives as they move through generic, even indifferent, spaces with no material trace? Or, as argued below: can symbolism be embedded in contextual morphological relations and in properties of the space itself? At stake in posing this question about what anchors collective memory is discerning the material dynamics of popular agency, outside the formal machinery of state and established powers. In David Harvey’s terms: how did the people enduringly register onto the square their “right to the city”—the right to imagine or to project their collective imaginations and desires onto the city’s fabric?[1] What follows attempts to draw on the square’s history and urban morphology to offer plausible speculations about the square’s sustained symbolic status, and what this reveals about the city’s symbolic political history.

The Clues from History: A Belated Ascendancy

How, did Tahrir Square first assume symbolic status? This is crucial to understanding how such symbolism evolved since then. The following narrative claims no more than sound plausibility at this point. Only thorough archival research of period newspapers, photography, literature and urban development projects can articulate Egyptians’ perceptions of Maydan al-Tahrir, confirming how the square first attained its status, and qualifying people’s evolving attachments to it.

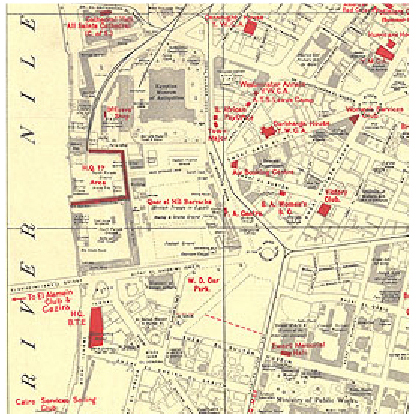

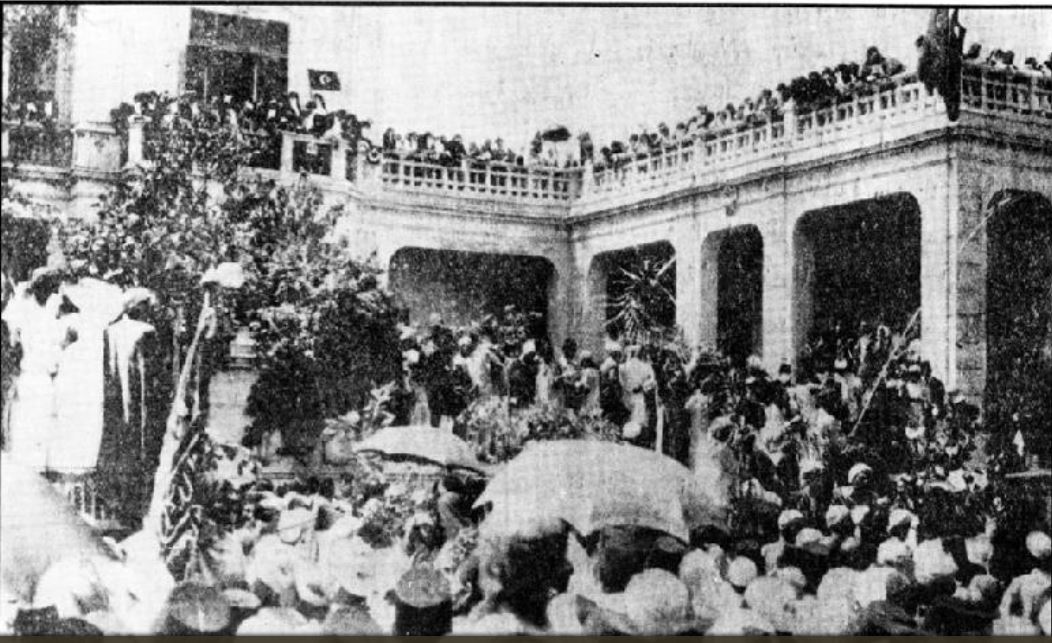

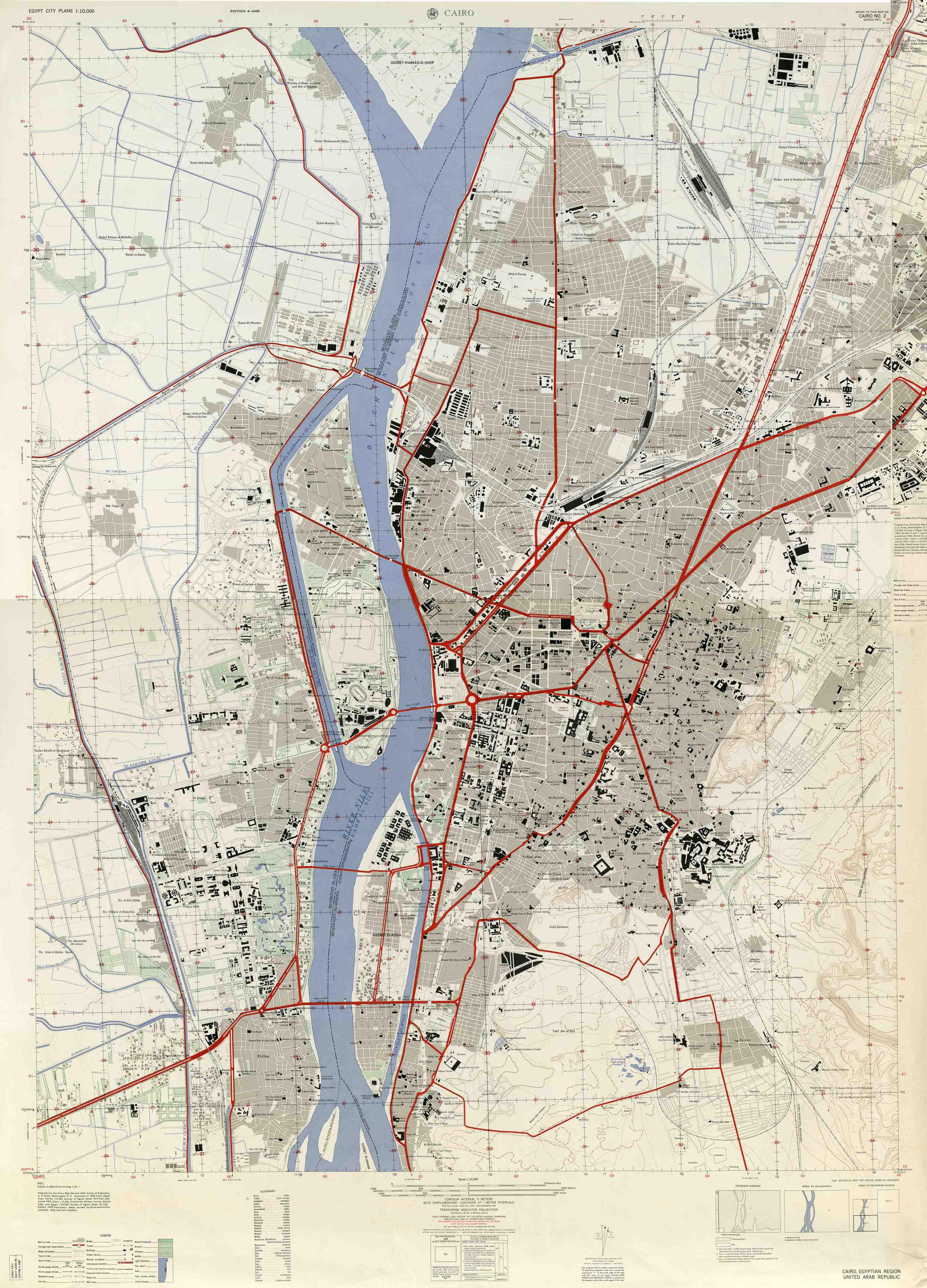

The earliest sizeable street action in this square one finds, in the British Foreign Office (BFO) archives, dates back to February 1946. Then, the square’s land-area was mostly occupied by the Qasr el-Nil British army barracks [Figure 1]. Gathered outside the barracks in Maydan al-Ismai’liyya (the current square’s southeastern corner), crowds angrily protested continued British occupation despite evacuation articles in the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty, and after stalled promises during World War II. Protesting crowds were attacked using live fire, vehicles charged into assembled crowds, protesters were killed. This marks the square’s incipient position in the city’s map of protest-sites which, until then, was dominated by other squares in different periods: Al-Azhar courtyard and surroundings were the main source of “disturbances” for the British from 1919 through the early 1920s. From there proceeded most processions towards other streets and squares. Maydan ‘Abdin was the site of numerous clashes during the interwar years and after World War II, when protesters marched into the square to voice their anger outside the king’s palace. Maydan Bab al-Ḥadid (later Ramsis), facing Cairo’s railway station, also witnessed numerous events, especially those involving arrivals or departures by dignitaries to other cities. But two squares held special significance as destinations or main gathering points: one, Maydān al-Opera in the 1930s and 1940s, as emphasized by the Palestine Post correspondent in 1935, and as evident in the BFO reports and period photographs. It was also the “frontline” with British troops in earlier demonstrations. Naguib Mahfuz’s dramatic finale for Palace Walk (1956) saw Fahmy, the revolutionary middle-son of a petit-bourgeoisie al-Gamaliyya family, killed by British fire during the 1919 uprising while approaching al-Ezbekiyya Gardens from al-Azhar’s direction. With numerous European establishments around, the British probably felt compelled to confront “rioters” there. [Figure 2] But while Maydan al-Opera was planned by Pierre Grand Bey as the city’s cultural-cum-business public space since the 1870s (with ‘Abdin as the formal square, Figure 3), the second significant spot evolved from the post-1919 anti-British struggles (until 1952): Bayt al-Umma (1919 revolutionary-leader Sa’d Zaghloul Pasha’s house, east of Qasr el-‘Ainy Street, Figure 4) and surroundings. This was the origin and/or destination of several demonstrations organized by the Wafd party and its youth affiliates, the Blue Shirts Brigade. Although hardly a gathering space for groups from all political affiliations, Bayt al-Umma attracted a relatively large and loyal following, especially amongst the Fouad-I (now Cairo) University students.

[Figure 1: Map of Cairo 1946, the vicinity of Ismailia Square: the British Army Barracks

and the Egyptian Museum (©The British Library Board)]

[Figure 2: Opera Square, Cairo 1947 (Image Courtesy of Al Lataif Al Musawara)]

[Figure 3: Abdin Palace and Square. Khedive Abbas Helmy’s Investiture1892

(Courtesy of the Memory of Modern Egypt Collection, Bibliotheca Alexandrina)]

[Figure 4: Bayt al-Umma, 1928. A protest by Wafd loyalists in response to the suspension of parliament.

(Courtesy of the Memory of Modern Egypt Collection, Bibliotheca Alexandrina)]

Thus, Cairo’s tradition of political events was established and active (from 1919 onwards), when British troops withdrew to the Suez-Canal area late-March 1947, and al-Ismai’liyya square was soon enlarged to incorporate most of the demolished barracks’ land. Other historical narratives claim the square’s emergence as a protest venue earlier in history—even back to the 1919 uprising, according to one government website. Numerous such claims, surfacing soon after February 2011, require careful vetting through archival research. But regardless of when Cairenes first protested in the square, 1947 must have been a transformational year, marked by the significant absence of the barracks, the subjugation they signified and the potential given by the square’s expansion. The people—as people, not as subjects—developed an attachment, not to its buildings or monuments, but to the square per se.

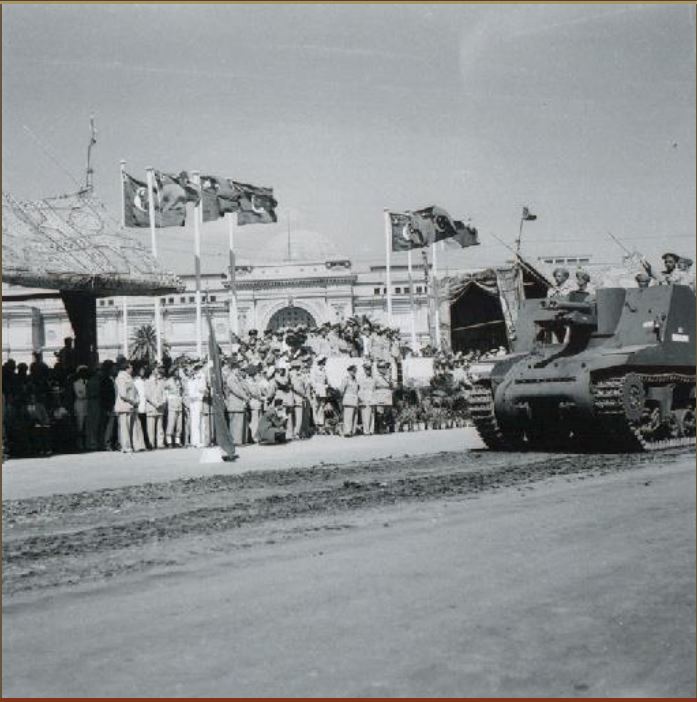

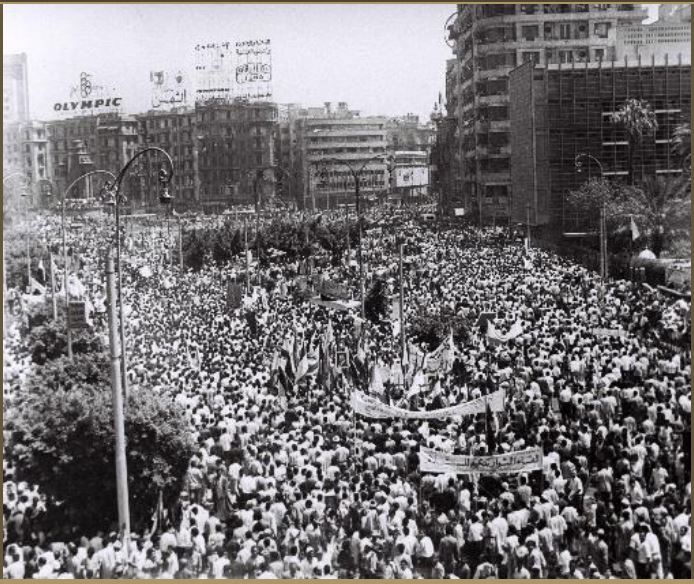

Yet still, opening up such a large square, symbolizing liberation from British occupation after long struggles and precious sacrifices, did not on its own entail its elevation to the foremost symbolic status. With increasing frequency after 1947, the square witnessed events, some of which were centered on, or even exclusive to, its grounds, including: a massive November 1951 gathering protesting British atrocities (albeit involving Maydan Bab al-Ḥadid, with destination to the Maydan ‘Abdin’s royal-palace); military parades in October 1952 and July 1953) organized by the Free Officers who grasped the reins of power in July 1952, and heavily attended by the public, and the Unknown Soldier’s Memorial (1953). [Figure 5] However, more street actions unfolded in spaces throughout the city-center, such as the January 1952 Cairo Fire, or with a clear epicenter elsewhere (e.g. protests against the 1947 UN Partition Plan of Palestine in Opera Square) where crowds were harangued by Arab leaders from a rooftop. The new square still had active contenders. Furthermore, this trend continued well into the mid-1960s. Despite numerous rallies and popular gatherings elsewhere, Nasser never addressed the masses in Tahrir Square. Locating the headquarters for Hay’at al-Tahrir organization in ‘Abdin (then al-Gomhuriyya) Square, he repeatedly favored it for public gatherings and addresses: hosting Eid prayers in 1953 and delivering a speech from the minbar afterwards, announcing the new constitution on 16 January 1956, addressing jubilant masses from its elevated balcony after the 1956 war, then again in 1961 after the Syrian secessionists broke up the fledgling United Arab Republic, and celebrating the July revolution’s anniversaries until 1964. [Figure 6] Unlike Opera and ‘Abdin squares, Tahrir Square does not offer an obvious rostrum from which to address cheering crowds. The square does not lend itself easily to the leader-masses rally format of gathering, and for which the establishment of Egyptian Television (1960) proved to be an even more apposite medium.

[Figure 5: Tahrir Square, October 1952. A Military Parade to celebrate three months after the July 1952 revolution,

with civilian participation. (Courtesy of the Memory of Modern Egypt Collection, Bibliotheca Alexandrina)]

[Figure 6: Gomhouriya (f. Abdin) Square, 1961: Nasser addresses the masses in after the Syrian secession

from the United Arab Republic. (Courtesy of the Memory of Modern Egypt Collection, Bibliotheca Alexandrina)]

It was starting in the late-1960s and early-1970s, when the relationship between charismatic leaders and mass-following became questionable, that gatherings reverted to people’s proclamations, polemics amongst protesters and/or confrontations with security force and that actions centered on Tahrir Square, thus edging it closer to its status as the people’s symbolic square. Such events included: spontaneous and/or organized marches in June 1967 [Figure 7] acknowledging military defeat but demanding Nasser stay in power (popular perception includes Nasser then mingling with demonstrators in Tahrir Square, as an older taxi-driver reminisced in Khaled al-Khamisy’s Taxi, 2009), contesting the lenient court verdicts on those responsible for military defeat in September 1967, the students’ Dignity Protests in 1972 (described by Ibrahim Aslan in Mālik al-Hazīn, 1983), and their earlier skirmishes, 1971, an October 1973 gathering to witness then-president Sadat’s victory procession towards Parliament, the 1975 anti-privatization scuffles, then the January 1977 bread-riots (after which Sadat organized a “popular march” to end under his Abdin (Gomhouriyya) Square balcony after passing through Tahrir Square—also in support of his trip to Jerusalem). The trend regains momentum from 2003 (the anti-Iraq-War protests), then again in 2006, culminating in the January 2011 events and its aftershocks.

[Figure 7: Tahrir Square, June 1967: Spontaneous and/or organized marches after the military defeat.

(Courtesy of the Memory of Modern Egypt Collection, Bibliotheca Alexandrina).]

Far from the smooth, predestined trajectory that romantic accounts maintain, Maydan al-Tahrir gradually, and rather erratically, evolved into the people’s center of symbolic expression from the late 1960s, and continues to the present. This is the historical phase that demands explanation. This essay’s question remains only partially resolved. Defined mainly by absences, of the barracks and main institutions, and of attachment to charismatic leadership, what then sustains the symbolism of this urban space? Are there undetected material-spatial qualities that beg a different lens?

The Square in Context

Clues from the spatial morphology of square and city, evident in current and historical maps, shed some light on how the square’s subtle spatial qualities ground its communicative role in the city’s symbolic politics.

The first set of clues comes from the square’s evolving centrality within Cairo’s expanding urban fabric. What was until the mid-nineteenth century a marshland amidst lakes peripheral to the fast-emerging European Cairo, was reclaimed by the 1860s, then gradually acquired an increasingly central position [Figure 8] with urban expansions on the Nile’s west bank (slow at first, but more rapidly since the 1960s) and the construction of Nile bridges: Qasr el-Nil Bridge (1871, rebuilt wider 1933), the English or al-Gala’ Bridge (1914) and Abbas II Bridge (1908). These bridges connected the two Nile banks closer to Maydān al-Ismāi’lia than to other squares such as Maydān Bāb al-Hadīd, Maydān al-Opera and Bayt al-Umma, even before Maydān al-Ismāi’lia became of comparable size and potential symbolism. This connectivity should be heavily weighted since it brought closer to the center of street actions one of the largest, and more active, groups of potential protesters: Cairo University students, whose activism overtook al-Azhar students’ by the 1930s. Even more than industrial and rail workers—the pioneers of strikes and street actions amongst Egyptians, and the emerging middle class of effendis—government employees and shop owners), students were the main provocateurs in recurring “disturbances” and protests (since the interwar years, as evidenced in the BFO reports).

[Figure 8: Expanded Cairo, 1958. (Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.)]

Thus, by the late 1940s onwards, and after the square acquired its current expanse, its relative location in the city had shifted dramatically to one of prime centrality and, given the numerous streets leading into it, high connectivity as well. This explains its centrality to most modes of transport (bus, subway-lines and private cars). As a square more frequently traversed by more people for their everyday journeys, its claim to “publicness” is heavily enforced, and its blockage by protesters or by security forces widely impacts the city’s transport systems.

Another look at the urban areas closer to the square shows another kind of centrality. With the removal of the British army barracks, the square became bereft of dominant state institutions overlooking it. Yet, a number of crucial institutions of power, while not on the square, are a stone’s throw away (or two or more configurational steps in Space Syntax terminology[2]) [Figure 9]. Parliament buildings sit a short distance away on Qasr el-Aini Street, while different ministries line that street further south of Tahrir Square. Unions, syndicates and political party headquarters dot the urban fabric east and south of the square, but none fronts it directly. ‘Abdin Palace, the seat of pre-1952 royalty, and Nasser’s Hay’at al-Tahrir from 1953 to mid-1960s, lie deeper unto the eastern urban fabric. The Ministry of Interior, arguably the state institution most influential in people’s lives, lies several blocks to the east along Sheikh Rihan Street. To the south in the Garden City neighborhood, are embassies of influential western countries: the American, British and Canadian delegations, with which Egyptians frequently have grievances. All the above existed in some form and to some effect prior to the 1947 transformations of the square and its later repercussions. Two more buildings were next added to extend the ring of institutions—disconnected but within reach. The NDP (Sadat then Mubarak’s National Democratic Party) building, previously the ASU (Arab Socialist Union, built in 1959), occupies the northwestern corner, but turned away from the square. Still to the northwest up Corniche Street stands another crucial institution: the Egyptian Radio and Television Union (the Maspero Building, opened 1960).

[Figure 9: Tahrir Square, since 1960: in context of surrounding institutions and arbiters of power. (By author, on an ArcGIS base-map.)]

Thus, in the communicative map of city and polity, the square acts like a forecourt to the institutional arbiters of power. On one hand, it is not usually subject to the peculiar security restrictions imposed by Egyptian security apparatus, and which are more rigid closer to buildings, or to physical boundaries in general. On the other hand, while not at their doorstep, the square’s voice and events cannot be ignored: they spill, or carry the threat to spill, towards such institutions in minimal time rendering the threat of mob action (always implicit in any large gathering) persistently imminent. Significantly, this peculiar configurational feature—proximate but not adjacent—characterizes the morphology of symbolic squares of other cities against their respective institutions of power, such as Paris’ Place de la Concorde (originally Place Louis XV), Washington DC’s Mall and others. These squares share with Tahrir comparable processes of historical-cum-morphological emergence as the people’s squares despite differences in political systems, but which all initially overlooked popular representation as an ingredient of the system.

The two kinds of centrality make Tahrir Square crucial to Cairo at large in its two forms of political practice: at the instrumental level of everyday practices, and at the level of symbolic representation. It converges millions of people as part of their everyday commutes, also bringing most Cairenes—whose voices are otherwise marginalized—quite close to the doorsteps of political powers. It is quite significant that the square’s role as a site for political gatherings gained momentum in the late 1960s, after the 1960 construction of the Maspero Building, from which the state dominated symbolic politics. Arguably, adopting Tahrir Square as their Maydan was an attempt by the people to reframe the state’s symbolic narrative about the nation.

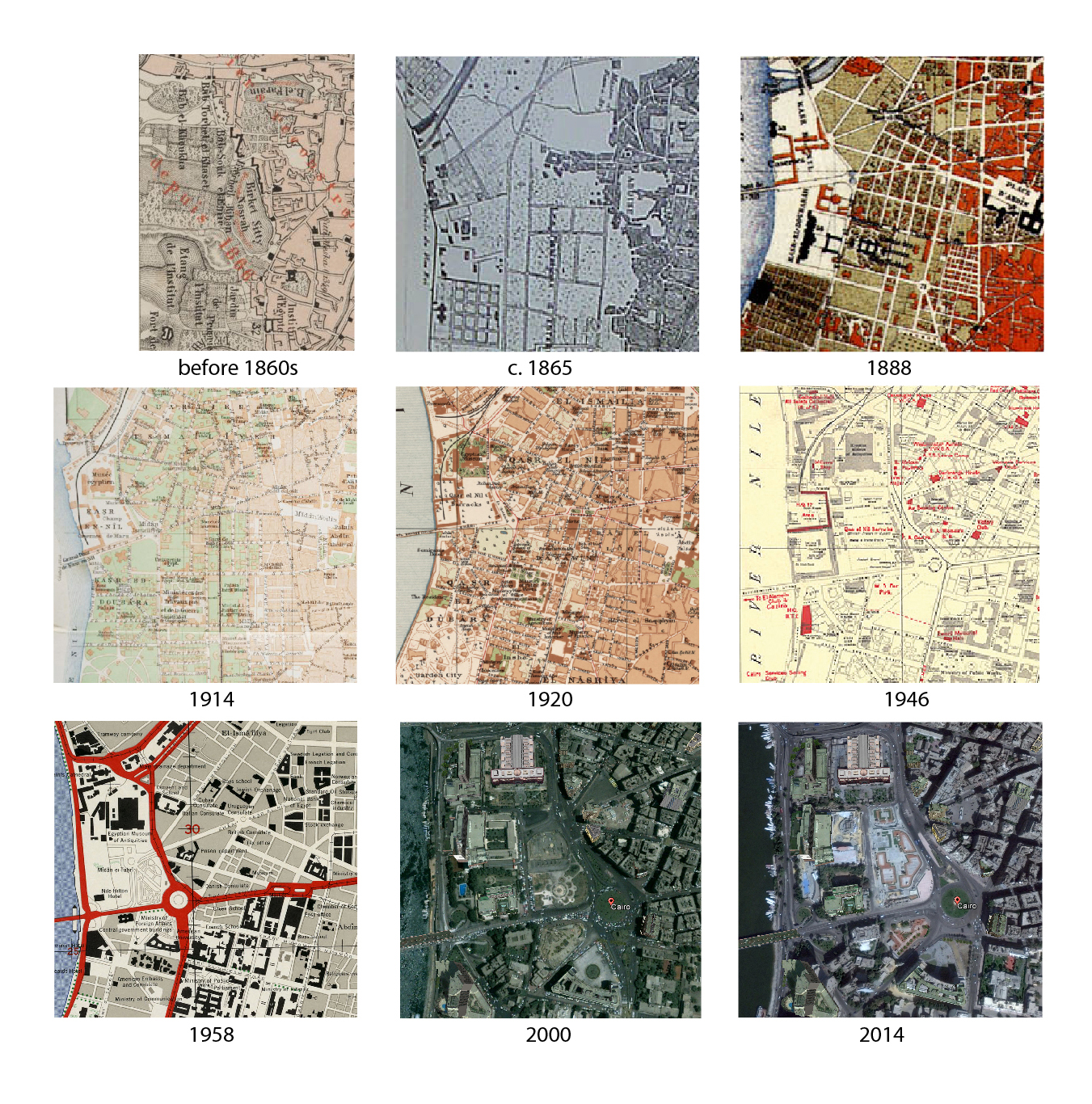

Another set of morphological clues is internal to the square itself. Since the 1860s, the square’s eventual extents were divided amongst four entities: Maydan Meret Pasha, Maydan al-Ismai’liyya, al-Koubri Street (Tahrir Street today), and the largest expanse belonged within the Khedieval Palace and Egyptian army headquarters—to become the British army barracks starting 1882. This last entity effectively broke the radial order extending from the east, and the linear plot-system from south and north. These conditions were maintained until 1947, when the barrack’s fences came down. Hence, what became Tahrir Square possessed no unifying order since its early phases. Its collage of urban conditions was neither cohesive nor dominated by any one entity. After 1947, when the geometries from east and south were partially extended into the square, they resulted in numerous weakly-resolved compositions over the years, as photographs and maps of the square since then demonstrate [Figure 10]. Significantly, while some arrangements offered park-space besides managing flows of bodies and vehicles in/through the square, no dominant axis or relation was sustained with any surrounding building(s). Even when attempted for the Egyptian Museum (1960s), the square’s irregular shape and order render any such relation partial.

[Figure 10: Tahrir Square: development of order; partial maps from pre-1860s to 2014. Pre-1860s, 1886 & 1914 (Courtesy Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA), Rice Univ.). Cairo c.1865: public domain (http://www.egy.com/maps). Cairo 1888: public domain PD-1923 wikimedia commons. Cairo 1920: public domain (Courtesy Library of Congress, USA & Maslahat al-Misaha, Egypt). Cairo 1946 (Bounds Map, ©The British Library Board). Cairo 1958 (Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin). Cairo 07/2000:Google Earth Satellite Image Fair Use (Image ©2015 DigitalGlobe). Cairo 10/2014: Google Earth Satellite Image Fair Use

(Image © 2015 Digital Globe)]

Thus, in form and configuration, the square’s surface remained persistently distinct from enveloping buildings—whose arrangements and orientations accrued over time to diverse sensibilities and inconsistent logics—echoing Cairenes’ attachment to the square in its own right. The replacement of the barracks with the Nile Hotel in 1959 maintained this “independence” of square from buildings. This is not to minimize the menace that global capital—as successor to military occupation—represents. But, along with other buildings around Maydan al-Taḥrir’s irregular expanse, the hotel is set back, thus maintaining the square’s formal independence. This kind of space resembles New York City’s Central Park: a social space around which buildings of different classes and functionalities stand at near-equal distance. Not despite of, but because of, such weak associations with any of its buildings, the space stands distinct from the power projected by any institution.

Moreover, Tahrir Square is also organized by an unresolved, and thus malleable order. It is an urban space conditioned by absences, not only of the barracks, the charismatic leader, and the dominating institution but also of a firm order. Because of such loose substructure of geometric order, the square is primed to absorb different spatial arrangements, and projections of identity (collective or sectarian) by ideologically diverse groups, without friction against the space itself. Hence, Islamists can hold their own “million-person” gathering there on 22 July 2011, only one day after a secular-dominated rally, and without being concerned about the square’s association with the Egyptian Museum whose ancient artefacts some of them hold in contempt. Rather like an inkblot, Tahrir Square accepts different even contradictory orders of imagination, particularly since none of them takes firm hold. As such, Tahrir Square presents to activists the challenge of obscuring differences in a society that underestimates its heterogeneity. One of the ephemeral accomplishments of the 2011 sit-in, from 28 January to 11 February, was to model practices for dealing with some of these social differences.

Mapping Affect

Does Cairo’s collective memory consist of ephemeral phantoms severed from material armature on the ground but relayed across generations in popular lore and literature? This essay presents the hypothesis that Tahrir Square’s symbolism manifests in a set of spatial relations, ingrained in the city’s morphological structure and deeply-rooted in its modern political history. Besides knowledge of the square’s history relayed (with unavoidable distortions) from one generation to another, such morphological properties are intuited by Cairenes as they go about their daily routines and/or take to Tahrir for political action. They read such structural political forces implicit in the city’s fabric, despite its opacity, drawing causal connections to their own conditions of everyday life—a reading that Frederick Jameson called “Cognitive Mapping.”[3] But in such a dynamic city, how long would such relations persist? Globally, the city is expanding at breathtaking speed, which threatens to dislocate Tahrir Square’s global centrality. Plans for relocating governmental ministries in a new administrative capital to the southeast of Greater Cairo are already under consideration, and if/when implemented despite staggering costs, and yet unresolved inconveniences to large numbers of employees, the square’s centrality amongst, and proximity to, institutions of power may be displaced. A new people’s square may well emerge in the proposed new city with Tahrir Square’s current configuration—close but not immediately adjacent to the new power centers—or an evolution thereof to complement forms of representation in the new urban setting. Although it seems that the current regime—given its repeated closures of Tahrir Square and its recent removal of the central bus terminal from it—has grown cognizant of this dynamic, and may try to preempt its resurgence in the new setting, this kind of square seems to emerge despite regime restrictions or mere indifference. The historical narratives of Paris’ Place de la Concorde and Washington DC’s Mall attest to this process of forceful emergence.[4] Tahrir Square itself, as argued earlier, inherited its symbolic status rather unpredictably from other squares in the city: Grand Bey’s planned Opera Square, and the emergent Bayt al-Umma. As Henri Lefebvre argued, urbanity is constituted by dynamic, intertwined and conflicting networks, incessantly re-configured as social stakeholders exercise their various, if unequal, powers to inscribe their will onto the urban fabric—and as the fabric itself exerts constraints and offers unforeseen possibilities.[5] The space of the city is what its social relations and power (im)balances are made of.

On the other hand, Tahrir Square has already weathered some changes. Since the 1990s, the center of gravity for symbolic politics through media has shifted from state-channels broadcast from Maspero in the square’s vicinity to the Media Production City (miles away in Sixth of October, western Greater Cairo), but this has hardly diminished Taḥrir’s aura. And while some protesters have occupied alternative squares over the past four years, Tahrir Square remains exceptional in its internal arrangements—its independence of surrounding buildings and its malleable collage of orders—and its centrality in the city’s global configuration, which is unlikely to change even with the extension of the new administrative capital. Ultimately though, one cannot avoid pondering that despite its status as the people’s space, Tahrir Square was chosen by the people but not made by them. The diverse forces that shaped it have yet to forcefully include the people’s agency.

Finally, perhaps this essay’s more significant proposition is to imply that there is a map of Cairo’s communicative and symbolic politics waiting to be charted—not only for the metanarratives of state and people(s), but also for the micro-narratives of everyday socio-economic politics. Such a map—or layers of mapping—would capture the shifting loci of gathering spaces across the city’s fabric and the urban configurations that attend them. It would help chart the chronology of changing meanings associated with such spaces and the dynamic social networks they construct around them. Its interpretations could potentially reveal the alternative urban realities dreamed by its activist communities as they marched to demand change.

Endnotes:

[1] Harvey, David, “The Right to the City,” The New Left Review 53 (2008): 23-40.

[2] See Hillier, Bill and Hanson, Julienne, The Social Logic of Space. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984) as well as Hillier, Bill Space is the Machine. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[3] Jameson, Fredric, “Cognitive Mapping,” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Nelson, Cary & Grossberg, Lawrence. (University of Illinois Press, 1990), and Jameson, Fredric Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991).

[4] This observation draws on ongoing research into the history of this type of political urban spaces in different contexts. To piece together the history of Place de La Concorde (aka Place Louis XV and Place de la Révolution) as a preeminent political space, the following sources were consulted among others: Bergdoll, Barry, European Architecture, 1750-1890. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000: 44-48); Ben-Amos, Avner, “The Sacred Center of Power: Paris and Republican State Funerals,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 22-1 (Summer, 1991):27-48; Jenkins, Brian, “The Six Février 1934 and the ‘Survival’ of the French Republic,” French History 20-3:333-51; Tilly, Charles, The Contentious French (Cambridge: Belknap Press 1986). For sources on the urban and political histories of the Washington DC Mall, see: Peterson, Jon A., “The Nation’s First Comprehensive City Plan,” Journal of the American Planning Association 51-2 (June 1985): 134-50; and Barber, Lucy G., Marching on Washington: The Forging of an American Political Tradition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

[5] Lefebvre, Henri, The Production of Space. (Oxford and Blackwell, 1991).

Resources:

Dhakirat Misr al-Mu’asira (Egypt’s Contemporary Memory). Bibliotheca Alexandrina Library Collection (03.12.2015)

Documentation relating to Egypt/Sudan 1839-1958 (FO 407/1-237). Confidential Print: Middle East, 1839-1969. The National Archives, UK. (03.12.2015).

Historic Maps of Cairo. From Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). (03.12.2015).

Palestine Post (1933-1950). Emory University Library Collections.

The Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection. University of Texas, Austin. (03.12.2015)